Ese tipo de errores sólo puede corregirse yendo de nuevo al campo, algo que no siempre es posible si los datos tienen que ser procesados lejos de él, como es a menudo el caso cuando se realizan muestreos biométricos u otro tipo de actividades de medición forestal en el trópico, e incluso puede ocurrir que el objeto medido ya no se encuentre disponible debido a que el muestreo realizado fue destructivo, o cuando el orden público provee sólo una estrecha ventana de oportunidad para visitar algunos sitios (o sea que sólo se puede ir al área por un corto tiempo cuando se sabe que no hay combates).

Ese tipo de errores sólo puede corregirse yendo de nuevo al campo, algo que no siempre es posible si los datos tienen que ser procesados lejos de él, como es a menudo el caso cuando se realizan muestreos biométricos u otro tipo de actividades de medición forestal en el trópico, e incluso puede ocurrir que el objeto medido ya no se encuentre disponible debido a que el muestreo realizado fue destructivo, o cuando el orden público provee sólo una estrecha ventana de oportunidad para visitar algunos sitios (o sea que sólo se puede ir al área por un corto tiempo cuando se sabe que no hay combates).Idealmente, las medidas tomadas en el campo, por ejemplo, altura del árbol y diámetro a la altura de pecho medidas en parcelas permanentes o temporales no sólo deberían estar salvaguardadas contra las mencionadas causas de error, pero también deberían ser actualizadas en la oficina o despacho en tiempo real, en la base de datos global disponible para el rodal, en caso que algo le pase a los datos en el camino y éstos se dañen (por la lluvia, por ejemplo), o se pierdan (hurto, naufragio, etc.)

Hasta hace sólo unos pocos años, habían pocas alternativas para la toma semiautomatizada de datos forestales de campo. Algunos anotaban los datos que tomaban en calculadoras científicas o en "data loggers", con los cuales era difícil la entrada y verificación de los datos a medida que el volumen de estos se incrementaba, siendo también grande la incertidumbre de si se podrían luego extraer los datos, lo cual dependía en gran medida de la vida de la batería del aparato, pues a menudo los datos se borraban cuando aquella se agotaba. Además, aquellos primeros aparatos eran pesados y difíciles de llevar al campo, tenían pantallas difíciles de leer en condiciones de campo y a menudo eran bastante caros y se hacían obsoletos rápidamente debido a sus interfaces y conectores demasiado especializadas, sin que se adhiriesen a un estándar industrial.

Todo eso comenzó a cambiar con el advenimiento de las computadoras de mano coomo los dispositivos Palm y Pocket PC, conocidos como PDA o asistentes personales digitales, todos los cuales comenzaron a entrar en el mercado (a precios relativamente razonables) en 1999. Las computadoras de mano pretenden poner a la disposición del usuario una funcionalidad de procesamiento similar a la de las computadoras de escritorio, portátiles (laptop) y tipo tablet PC a una fracción del tamaño, si bien no siempre del precio. Por supuesto, ciertas funciones tenían que ser reducidas para caber en un tamaño menor, siendo la más obvia el tamaño de la pantalla y la capacidad y la velocidad de almacenamiento/procesamiento. Igualmente, los programas que corren en un computador personal común no funcionan directamente en los PDA, y viceversa. Estos emplean un subconjunto reducido (y modificado) del sistema operativo de las computadoras de tamaño "normal", pero el procesador es algo diferente, por lo que requieren software especialmente escrito para ellos, y aun hay ciertos aspectos por estandarizar entre fabricantes, pero en sí lo aparatos hoy disponibles se encuentran muy estandarizados en cuanto a la transferencia y comunicación con computadores "normales" se refiere.

En el mercado de los PDA, los dispositivos Palm están ligeramente más extendidos entre el público en general. Sin embargo, en el ámbito empresarial se utilizan más los Pocket PC. Pero para algunos usos industriales (como el trabajo de campo forestal), las Pocket PC comunes no son lo suficientemente resistentes para soportar condiciones de intemperie y trabajo pesado, es decir, no están diseñadas para resistir caídas al suelo, funcionar en entornos húmedos o polvorientos, soportar salpicaduras o incluso inmersiones cortas en agua, o funcionar por toda una jornada de trabajo con una sola carga de batería. Para este tipo de entornos existe lo que se denomina el mercado vertical, que consiste de dispositivos más robustos diseñados para ser manejados menos delicadamente y existen estuches especiales para hacer que incluso Pocket PCs comunes puedan soportar condiciones de campo. Hemos entonces alcanzado una etapa en la que la toma semi-automatizada de datos de campo no sólo es posible, sino verdaderamente alcanzable y deseable.

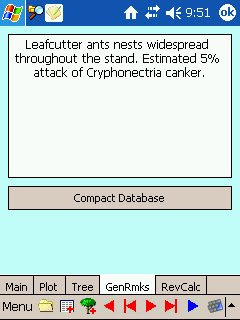

En este blog se discute el desarrollo de un sistema de captura de datos diseñado para aplicaciones de inventarios forestales, con el cual se busca capturar a mayor parte de los errores en que pudiesen incurrir los usuarios, disminuyendo además las etapas del proceso de toma de datos, haciéndolo menos complejo y por lo tanto menos propenso a errores. Se ha estado probando una versión inicial del sistema en el campo desde 2003 en Colombia por Silvano Ltda., una firma de consultoría forestal especializada en medición forestal y ahora se está expandiendo el programa para incluir funcionalidad de navegación y cartografía digital. Nuestra meta aquí es recibir comentarios de posibles usuarios.

.bmp)

.bmp)